|

This book is about the quest for lost riches. Since I was a child, I have been fascinated by the idea of finding lost treasure. My favourite books when I was growing up were Treasure Island and King Solomon's Mines, which I read and then reread repeatedly. I would spend endless hours imagining where and how I might discover some hidden treasure horde, and how golden coins would feel running through my fingers. My friends and I would roam around the neighbourhood where we lived, imagining ourselves on quests for fabulous lost art, treasure hordes or buried and forgotten riches. Playgrounds would become the ruins of ancient civilizations; hills would transform into the tombs of the Pharaohs and nearby parks would play the part of the deepest jungles of Africa. When inclement weather didn't permit our treasure-seeking, I would entertain myself by making maps all day. They would always be maps to some hidden stash of gold or pirate booty that I had imagined, and I would recklessly scrunch them up when finished to produce deep creases and folds, and then add stains of cold tea before carefully baking them to create what seemed to me as a pretty fair representation of an antiquated parchment. It could get pretty dull always to seek and never find, so from time to time I would raid my father's coin box and pluck spare quarters, nickels and dimes to make a personal little treasure horde. Gathering all the coins together, I would pick a spot somewhere in the neighbourhood and either bury or hide them, and then create a new map giving directions and clues to where to locate this unique and secret cache of hidden wealth. On hot summer days, I would gather some local kids together present them with the opportunity to "find" enough money for a cold drink or candy and then watch them as they tried to decipher the treasure map and retrieve my hidden coin stash. All these years later I still wonder if all the hiding spots were eventually discovered or if we missed some, possibly leaving them to future generations of children to find. All of this is to say that dreams of discovering lost ancient treasures have been with me all my life, and followed me into adulthood. Some might call it a healthy obsession. I call it a fascination. I am not alone with my daydreams of hidden gold and instant wealth. In fact, throughout our popular culture (and indeed our mythology) similar desires are well-represented. Look at our movies - how many revolve around a quest for a lost artifact, a search for hidden riches or a secret that would bring great personal power to the finder? Disney, in particular, has made a successful franchise from tales of the pirates who roamed the Caribbean seas, raiding the gold carried out of the New World by sailing ships and hoarding it in hidden treasure troves. It was the swashbuckling pirate captain I was always trying to imitate with my tea-stained treasure maps on which "X" forever marked the spot.

Movies are just the medium of modern mythology, and they are reflections of our ancient myths. Think of the quest for the Golden Fleece by Jason and his Argonauts, or the 2000-year-old story of the search for the Holy Grail. Myth and legends give us countless examples of the desire to find what has been hidden, and permeates our culture from some of the earliest accounts of human history and storytelling. From El Dorado to Excalibur, we are obsessed with the finding of long-lost treasure, if not for the wealth then for the completion of the search itself. I decided to write this book to explore some of the lost treasures that fascinate me the most. There is no shortage of material out there, and as I began to research my list, I realized there was a particular kind of treasure that intrigued me more than the rest. While mythology is radiant with great stories of exotic artifacts and enormous piles of gold, they somehow can't quite capture the imagination like historical treasures do. Perhaps some of them may have existed in one form or another, but there is something more compelling about the possibility that a treasure is real and could be discovered and taken into our hands – touched, felt and taken. I decided to apply two criteria to the treasures I would explore in this book and their stories. First, I will not delve into anything that is purely based on myth. For example, the Golden Fleece may have been strictly allegorical, or the tale of this artifact may have had its origins in the rather mundane ancient practice of straining mountain streams for gold nuggets and flecks using the fleece of sheep to catch them. It is probably safe to assume that it wasn't a magical sheep skin belonging to a god and that in this capacity, it never existed. This book is concerned solely with those treasures we know to have existed, either through documentary or archaeological evidence. The magic of the stories I will explore is that they are all human-made; their value comes from the skill involved in their making - skills which in many cases are now lost to us. Also, they are unique in the historical context to which they belong; the role played in past events or the symbology of the objects themselves to the culture to which they belonged. My second condition for inclusion in my list is that all of the treasures described here are gone. Through the ravages of war, accident, an act of gods or men or for reasons wholly unknown, each of these treasures has been lost to the world and remain missing. What remains are the stories, descriptions and accounts of them – just enough to tease us about what we once had and have no longer. Most of them are likely never going to be found or seen again, but maybe – just maybe there might come a day when in some old, dusty attic or a box at a rummage sale one of them might come back into the world and be rediscovered again. Any loss must always be paired with the promise of hope, what has gone missing might be returned and no longer lost but found instead. I hope that this comes true for the treasures detailed here and that they pique some interest as well in the reader. As I was compiling my research, my list swelled to grow much larger than I had anticipated it would be; history is resplendent with missing valuables of one type or another that have continued to remain compelling long after they disappeared. I have tried to present some of the fascinating here for you, their stories and what we know and sometimes don't know about what happened to them. While not all are artifacts of gold and precious stones or necessarily have any monetary value to them, they are all lost treasures. Some have their origins rooted in the ancient world, while others have more modern stories. All are of great significance; cultural, religious and artistic. Most importantly, while we may know a great deal about the items themselves, the whereabouts and continued existence of all of them is shrouded in mystery and conjecture. I hope one day you find one of them. -Mark Rodger

0 Comments

About two years ago, I was in Casablanca, enjoying some Tangine and assorted salads at the Sqala Cafe Maure. Nestled in the ochre walls of the sqala, an 18th-century fortified bastion near the marina, it served as inspiration for one of my favorite warriors.

My host, Driss, a Casablanca area businessman, and I were discussing the various warriors that made up History's Greatest Warriors Volume 1. He asked me about Dihya, and why I hadn't included her in the book. "Dihya?" I asked. I hadn't heard of her yet. Driss went on to describe a warrior Queen that was an inspiration to the Maghreb culture of North Africa. After hearing his description of her exploits, I knew right then and there I needed her story in Volume 2 of History's Greatest Warriors. I hope you find her story just as fascinating as I did. -Johnathan DIHYA “Algerian Warrior Queen” While Joan of Arc stands out in the minds of most as the most famous example of a brave and religiously-inspired woman-warrior, few of us have heard of Dihya. A mighty Queen Warrior, she was a kindred spirit to Joan of France and defended her country and religion vehemently back in the 7th century. Born in the mountains of modern-day Algeria, Dihya is purported to have been a member of royalty and destined to become the Queen of the Aurés. Although little is known of her parentage, according to the Arab historian Ibn Khaldun her mother was a member of the Jrāwa tribe who went by the name of Tabita or Mathia ben Tifan – daughter of Tifan. As a Jrāwa, Dihya would have been considered a Berber, although this term has been rejected by the Amazigh people throughout history. The Amazigh people populated much of North Africa from as earlier as 5,000 BC and commanded considerable respect for their military competence and excellence with horses. Calling themselves Amazigh, possibly meaning ‘free men’ the Berbers integrated with the Phoenicians of Carthage, living alongside them in an uneasy peace for many years. The Israeli writer and translator Nahum Slouschz suggests that Dihya was a descendant of a wealthy and noble family, deported from Judea. According to Slouschz’s version of events, King Josiah instigated the Deuteronomic Reform, removing idols, destroying cults and establishing the Temple of Jerusalem as the focal point for all worship. In keeping with the Bible’s Book of Deuteronomy, the reform stressed the notion that only one God should be worshipped, reinforcing the concept of monotheism. Slouschz describes Dihya as “a descendant of a priestly family” ; as priests exist only in the Anglican, Catholic and Orthodox churches, her family didn’t necessarily support the strict Judaism of Josiah, and this might have led to their deportation. Although some sources indicate that Dihya was Jewish by birth, it seems more likely that she converted to Judaism with the rest of her tribe earlier in the century. Historically the Amazigh people held a variety of religious beliefs, with some being Jewish, others Christian and still others adhering to an ancient polytheist set of beliefs. Although Dihya has been depicted as a leader faithful to the Judah religion, some claim she was a Christian who took strength from the image of the Virgin Mary. Others suggest that she practised an indigenous religion which worshipped the sun and moon which resonates with her reported prophetic powers better than either the Christian or Jewish religions. Whatever her beliefs, Dihya was brave and determined while facing the rise of Islam in Africa, perhaps partially due to the denigration of women within the Islamic religion which would have undermined her authority and status. Little is known of her childhood, although there have been suggestions that she developed an early interest in desert birds. While this seems a trivial footnote in her life, her studies significantly advanced biological science in North Africa as well as contributed to her reputation during her lifetime as a sorceress who could foresee the future by speaking to the birds and animals. As with everything relating to Dihya, there are many different versions of events that revolve around her; even her name is debated. Some refer to her as Dahiya while other scholars name her as Tihya or Dahra. All the records we have of her life are often controversial and contradictory, full of legend and folklore with a few facts sprinkled in. Like her religious beliefs, Dihya’s tribal origins are equally unclear with some suggesting she belonged to the Lūwāta tribe rather than the Jrāwa. Regardless of the lack of clarity regarding her origins, Dihya established herself as a powerful leader who united disparate Berber tribes to fight for their cultural and social independence, refusing to be subjugated. Prior to leading her own army into battle, Dihya fought alongside Aksel, the king of Altava and chief of the Awraba clan; according to some sources he was her father. During these battles, Dihya proved her capability as an adept soldier and astute military commander. Aksel led the Byzantine- Berber army into battle against the invading Arabs, plotting their defeat after pretending to join the Arab side. According to some, Aksel converted to Islam as a ruse to lure the Arabs into a false sense of security that enabled Aksel to ambush their weakening army. It seems Aksel believed that converting to Islam would be profitable for him, but as the Muslim influence and army grew in strength, Aksel’s own position of sovereignty looked certain to come to an end, and he was encouraged to abandon his adopted faith and return to his religious roots. The Berbers fought many invading forces over the years, and their violent response to the Islamic invasion was possibly not fuelled by religious beliefs. Fanatically independent, they had been subjected to Roman rule and were determined not to be conquered again. The invasion of the Arabs into their lands was resisted ferociously, and they saw the conflict with the warriors of Islam as a mere “continuation of a fight against the Romans”. It is highly probable that Dihya joined the battle against the Arabs around the time of Aksel’s reversion to Judaism, just as many of her fellow tribal members did. Ibn-Khaldun suggested that the conflict between the Arabs and the Amazigh was another form of the struggle between nomadic and settled people repeated throughout history, rather than a fight with origins in conflicting beliefs. Regardless of her motives, Dihya was a determined and effective soldier, earning herself widespread respect and authority. Late in the 7 th century, chief Aksel was captured by Arab soldiers and forced to disband his army. After his release or escape, however, the king of Altava went right back to fighting and reformed his army to take on the Arabs once again. This time, he succeeded in defeating them and killing their leader, Uqba ibn Nafi. Upon his death, Aksel was succeeded by either his wife or another female relative, but the ruler of the successor was very brief. By around 690 AD, Dihya became commander of the Berber army. Having already proved her worth as a soldier, Dihya cemented her reputation as a formidable military opponent. When the Islamic troops returned to invade again under the command of Hassan ben Naaman, they were prepared for renewed bitter fighting with the Berbers, but they didn’t count on Dihya. Invading with 45,000 soldiers, Hassan was supremely confident of victory, especially so when he learned that he was opposed by a mere woman. Dihya first attempted to use diplomacy to neutralise the Arabs, but all offers of a negotiated peace were dismissed and refused. Instead, Hassan responded with his own ultimatum advising that he would grant peace only if Dihya converted to Islam and recognised the supremacy of the Muslim authorities. According to some sources, Dihya stalwartly refused with the declaration “I shall die in the religion I was born to”. In an entirely polemic version of events, French historian Henri Garrot suggests that Dihya actually converted to Islam rather than confront the mighty force of Hassan, but the Arab leader advanced to attack her army anyway. Mubarak Milli rejects this theory, claiming Garrot simply wanted to discredit the great Amazigh queen while suggesting that the Islamic invasion brought stability and prosperity to the region. Another source provides evidence consistent with this belief, suggesting that Hassan sent an envoy to Dihya demanding that she accept Islam as the religion of her people. When Dihya refused, Hassan’s representative explained that they wanted to bring the Amazigh people into the light of Islam. Dihya again challenged him saying that she has read the Koran but found “nothing new in it” and that it seemed somewhat regressive “especially in regards to the relations between men and women”. Inevitably this sparked a heated argument about the status of men and women, and reportedly Dihya angrily retorted “I am not inferior to you and you are not my equal!” In this version of events, Dihya is as familiar with the premises of the Islamic religion as she is both Judaism and Christianity, although it is the latter that she has embraced. Hassan’s envoy becomes enraged at her refusal to accept what she refers to as his “false prophet”, and called her “a witch and a sorceress”. Her supporters counselled caution, but Dihya remained defiant and pointed out that if they converted to Islam, her people would lose both their lands and their freedom, which was ultimately the same fate they faced if they were defeated in battle. Declaring that they had nothing to lose and everything to win, she reasoned that the Berbers would need to fight. It would seem that Dihya’s faith, loyalty and her apparent ability to speak with animals and foresee the future swayed many of her people. Berbers from all over the region came together to join forces with the woman they called Kahina, meaning “the diviner, the fortuneteller”. Although some have asserted that Dihya’s reputation as a sorceress was bestowed on her by her opponents, others contend that her gift of prophecy gave her the capacity to predict the exact formation of opponents’ troops, the direction of their attack and the source of their possible reinforcements. Inevitably this inspired her fellow Berbers and, although her victories were hard-won, they were nonetheless decisive. Some accounts suggest that although her forces were significantly outnumbered by the Muslim army, Dihya was able to secure an unlikely victory by using her knowledge of the environment. Realising the untenability of her position, Dihyahad ordered a retreat. However, as she perceived the strong winds blowing in the enemy direction she ordered that large fires be set, sending great clouds of smoke at the Arab soldiers. This stopped the enemy advance, but also obscured her forces from Hassan and his men. Strategically, it also meant that to launch another attack the Arabs would have to cross a great swathe of burnt wasteland with no resources at hand. Hassan promptly retreated and spent the next five years in Egypt, licking his wounds and preparing for a second invasion. There is evidence that indicates the success of her fire-brand approach inspired Dihya to instigate a scorched-earth policy that would, in time, prove disastrous both for her and for her people. Believing that the Arabs were primarily after the riches her land had to offer them, Dihya decided that by destroying everything of worth she would dissuade the Arabs from further invasions. Historian Edward Gibbon records the Berber Queen as urging her people to destroy all their precious metals and raze their cities so that “when the avarice of our foes shall be destitute of temptation, perhaps they will cease to disturb the tranquillity of a warlike people”. Dihya began her campaign by burning productive fields and melting down precious metals, before going on to tear down cities and towns and destroy all fortifications. Sadly, although this may have made the Berber lands less attractive to invaders, it also meant that the livelihood of her own people was seriously compromised. With no hope of growing food in their charred fields and blackened orchards and with no roof over their heads, many town and city residents became nomadic and wandered through the barren wasteland left after years of war. Inevitably, this damaged her reputation and popularity considerably... if it was true, that is. Gibbon is pretty scathing in his treatment of the Amazigh queen, saying that her policy of “universal ruin” probably terrified those city inhabitants who shared neither her beliefs nor her nomadic upbringing. According to Gibbon, she was an unworthy leader who based her powers on “blind and rude idolatry” and the “baseless fabric of her superstition”. Others, however, are suspicious of claims that Dihya was responsible for the scorched-earth policy, pointing out that it was a technique the Arabs had used previously in both Libya and Egypt. The Arabs found this was an effective way of subduing the enemy population and as they were more concerned with recruiting people for religious conversion than winning great territories and riches, this was a successful approach. If the Arabs did instigate the scorched-earth policy, it proved effective even if many historians have attributed the blame to the Berber Queen. Regardless of who decided on the tactic, it certainly had the effect of demoralising the people and all but destroying their faith in their sorcerer queen. For many, a Muslim victory seemed inevitable, and perhaps even Dihya herself doubted her capacity to continue resisting the Arabs. Some even suggest that she later surrendered one of her own sons to Hasan . Unlike the morally pure Joan of Arc, Dihya was a passionate woman who was “addicted to the lusts of the flesh with all her youthful flaming temper”. She had two sons by two different men and apparently had three husbands on hand to satisfy her carnal needs. Rumour has it that just as she surrendered one of her own sons to Islam, she subsequently adopted one young man from amongst the Arabic prisoners she captured during her conflicts with Hassan. In a strangely generous act, Dihya was known to favour releasing any prisoners she took, but this one enemy soldier named Haled ben Yazid she took as her own son. Little is said of Yazid after this event, but another son seems to have played an instrumental role in her eventual defeat. According to some sources, when the invading Arabs returned amongst them was one of Dihya’s own sons who had turned away from Judaism and converted to Islam. Although it is unclear as to whether the returning Muslim army was lead by Hassan or his successor Musa, their defeat of Dihya is not in dispute. Assuming that Hassan was leading the Arab army with Dihya’s son by his side, the Berber queen he found waiting for him in the Aures mountains was a very different woman to the one who had defeated him some years before. Either as a consequence of the scorched-earth policy or through bribery and corruption, many of those who had stood behind the Dihya had defected to Hassan’s army, leaving her heavily outnumbered. To further her disadvantage, her traitorous offspring knew her usual methods and was able to inform Hassan on her probable tactics. With so much against her, it’s hard to believe Dihya even bothered to engage with the opposition at all, but she did, and her small army fought so bravely and with such ferocity even their enemies couldn’t fail to admire them. As any true warrior should, it is believed that Dihya was killed sword in hand fighting for her beliefs and her country. She was decapitated, and her head was given to Hassan as a prize of war. Reportedly out of respect for his former opponent, he went on to take good care of her sons, bringing them up as his own and giving them the tools to follow in their mother’s footsteps, leading their own armies into battle. Things weren’t so good for the Berber people after Dihya’s defeat and death; thousands were sold into slavery by the victorious Arab oppressors. Those few that stayed free ended up in isolated communities, holding out as long as they could against the formidable Arab onslaught. Some are said to have taken their own lives rather than convert to Islam, but by around 750, North Africa was almost exclusively Islamic, with little of Dihya’s Jewish legacy remaining. Despite this, Dihya has proved an important figure for a variety of people and cultures. Noted author and historian Abdelmajid Hannoum stated that “[N]o legend has articulated or promoted as many myths, nor served as many ideologies as this one”. Dihya has been reborn and reinvented numerous times, serving as a figurehead for the Berbers and ironically, even the Muslims. According to some Muslim believers, Dihya didn’t die on the battlefield but was rather defeated, after which she converted to Islam and became a model Muslim. This seems a highly unlikely outcome. Nevertheless, over the past 10 centuries or so Dihya has been adopted by a wide range of different political and social groups with diverse agendas covering everything from Berber cultural and ethnic rights to feminism and Arab nationalism. The Arabs often present her as a woman in possession of supernatural powers but who eventually, recognised the legitimacy of Islam, went on to encourage her sons to adopt the religion and create unity between the Berbers and their former enemies. Part of Dihya’s chameleon capacity appears to have come from the Berbers’ own fluidity when it came to religious beliefs. According to Ibn Khaldun, the Berbers adopted the beliefs of pretty much every group of people that ruled over them, first adopting Judaism while under the influence of the Yemen kings before swiftly switching to Christian beliefs following the Roman invasion. Such changeability has meant the legend of Dihya could be claimed by virtually anyone, although it is as an example of the Berbers’ religious, gender, and ethnic tolerance that she is most remembered. Dihya has been so celebrated by the Berber people that a statue of her was erected in Algeria as recently as 2003. Built by Amazigh activists, the 9-foot monument was constructed as part of a movement to preserve the remains of what they believe to have been a fortress erected by Dihya during the Muslim invasion. Far from uncontroversial, however, the unveiling of the statue was ignored by the national press, even though the Algerian president Abdelaziz Bouteflika attended the ceremony. Cynthia Becker suggests that Bouteflika’s presence was designed to appease the activists while the lack of press coverage was at the instigation of the government, suggesting a conflict of interest . For some, the defiant woman warrior immortalised in the effigy represents a period of history and religious activism they would rather forget. Given that the Amazigh are now Muslims, some see the statue as an act of blasphemy, celebrating a woman who strongly resisted their own religion. Indeed, Dihya has been celebrated as a “prototypical antihero, representing everything counter to Islamic values”. Although in more recent times, Dihya has been taken to symbolise feminism amongst the Amazigh people, she also embodies the ethnic rights of this small populace. Certainly during her lifetime, the Amazigh enjoyed relative freedom and women were allowed leadership status – a relatively unusual aspect of any culture at the time. Not only was ancestry traced using the female line, but property was also passed down from daughter to daughter. This would come to an abrupt end with the introduction of Islam to the region, but Dihya’s dramatic attempts at protecting her people have never been forgotten. It is notable that many powerful women have been associated with having some kind of supernatural powers, and Dihya is no exception. Not only is she described as being unusually tall and "great of hair", but legend also suggests that she lived for over 100 years and when she was inspired would let out her hair and beat her breast, suggesting a state of religious ecstasy. In addition to her prophetic capabilities, it has also been suggested that the Kahina’s revolt against the Arabs was foretold by the appearance of a comet. Legends and rumours have also swirled around Dihya’s private life, suggesting that she married twice, once to a Greek and once to a fellow Amazigh. In another story of Dihya or, on this occasion, Dahi-Yah, the beautiful young woman is ordered by the leader of another tribe to become his wife. Initially, she refused, but when the chieftain went on to intimidate and massacre her tribe, she relented and married him. The tribal chief was an unpleasant man who forced himself on her and beat her prior to their wedding. On their first night of wedded misery, however, Dihya took her revenge “smashing his skull with a nail” and ending his tyranny. Whatever Dihya was, in terms of religion and power she has firmly established herself as an icon and symbol of the Amazigh people’s refusal to be subordinated or converted into this or that set of religious beliefs. To this day, Dihya remains an important and popular figurehead for Berber activists who feel her power and position not only emphasises the gender equality of their culture but also their liberal beliefs and willingness to accept people of all ethnic and religious origins. The Amazigh people continue to fight for recognition as a distinct political, ethnic and linguistic group. In certain places like Libya, even speaking the Amasizgh language can lead to arrest and charges of espionage. Meanwhile, in Morocco, the Amazigh continue to fight against both economic deprivations and to have their native tongue Tamazight recognised as an official language alongside Arabic. It is little wonder then that a woman who was prepare to put her life on the line to secure independence and freedom for her people should continue to be celebrated among the Amazigh. Many girls are named for the Berber Queen, and her image appears regularly in the crude graffiti of Amazigh activities, serving as a visible symbol of self-determination, resistance, and freedom. History's Greatest Warriors is available on Amazon as a digital download or in paperback on most online bookstores. What they look for Almost every kind of body in the universe transmits energy (except black holes, which absorb energy and refuse to allow it out again. But more on that later in this book). The energy is transmitted in waves and the wavelength determines how people on earth “see” the energy and what name they give it. The light waves picked up by optical telescopes and the light waves picked up by radio telescopes are on the same spectrum but at different places – it is the length of the wave that determines where the source sits on the spectrum. A possible confusion that should have been removed by that last paragraph is between light and sound. The waves picked up by a radio telescope are not – despite the word “radio” in radio telescope – the same as sound. Radio telescopes receive a form of light wave, and not sound waves. Light can travel through a vacuum, and sound cannot (which is why, when you scream in space, no one hears). There are also differences in the shape of the wave; light waves are transverse and sound waves are longitudinal. The fact that everything is transmitting energy, and transmitting it in every possible direction, means that the universe is a very noisy place and it is very difficult to pick out the specific kind of signal that SETI is looking for, which is signals that raise at least the possibility that they were generated by intelligence. The radio frequencies used on earth lie between 20 kHz and 300 GHz, but the whole radio spectrum is a lot bigger than that – it runs from 3 Hz at one end of the scale to 3 THz (3000 GHz) at the other. Signals being generated by heavenly bodies simply because they are heavenly bodies take up the whole of that radio spectrum. SETI’s scientists think it is extremely unlikely that any intelligent being would attempt to signal over such a wide range, and what they are looking for is primarily narrow-band signals (signals covering only a small part of the radio spectrum). They also look for brief flashes of light – and by brief they mean flashes that last nanoseconds. Signals meeting both of these criteria – narrow-band radio spectrum signals and flashes of light lasting nanoseconds – have been discovered. What happens then is that they are considered possible candidates for intelligent signals and examined in greater depth. Scientists are also aware that picking up a radio signal would not necessarily indicate that it had been intended for us. Some signals, if strong enough, may simply have left the planet’s atmosphere and reached us although no intention existed that that should happen. The same thing may be true in reverse; somewhere out there in space may be a civilisation that is trying to extract intelligent messages from chat shows and reality TV originating on earth. And that raises one of the problems with the SETI Project: if they succeed in identifying a signal as definitely originating from an intelligent life form, how likely is it that they will be able to decode the message? As well as looking for communications or signals beamed into space, and those seemingly intended for Earth, SETI also looks at signals passing between two worlds where the line of sight extends to this planet. Such signals may be messages between a planet and another planet or a satellite, and may continue past the intended receiver and eventually reach here. It’s possible to reason that an intelligent life form capable of sending signals into space is also capable of reducing them to the barest minimum in order to make them comprehensible to a different civilisation. That won’t be the case if the signal represents a message between two places sharing a common language. What stage has SETI reached? Here are some interesting points from current and recent searches. FRB121102 is, as the letters FRB in its name indicates, a fast radio burst. FRBs last for perhaps a millisecond, but the energy emitted in that millisecond can be as much as the sun has given out since the first wheat and barley were cultivated some 10,000 years ago in what was then Mesopotamia and is now Iraq. Scientists argue furiously over what causes an FRB and the fact is that no-one knows. Probably, they have a variety of causes. Possibly, one of those causes is the desire of an intelligent life form to transmit a signal. A number of FRB’s have been found; 121102 was first seen in 2012 at the Arecibo Observatory in Puerto Rico. It was seen to recur a number of times, and a team at Cornell University led by Dr Shami Chatterjee made arrangements to watch in case it returned. That’s one of the risks in this kind of work, because it might have been a century before 121102 came back to life; in fact, however, there were nine flashes in six months (and there may have been more, because only 83 hours were devoted to observing the location of the pulses during those six months). Doctor Chatterjee was previously a Janskey Fellow at the Harvard-Smithsonian Centre for astrophysics and it was at the extremely powerful Carl G Janskey radio telescope array that the pulses were observed. Doctor Chatterjee’s team was able to locate 121102 in a dwarf galaxy more than three billion light years distant from Earth. Does this mean that the dwarf galaxy is home to intelligent life? It does not mean that at all (and nor does it mean the opposite, which would be that there is no intelligent life in that galaxy, or that these flashes were not sent by intelligent life. There is simply not enough information to say one way or the other). It is, though, helpful in ruling out some of the other possibilities that have been considered. One widely held view of FRBs was that they were formed as a result of some cataclysmic event – the collapse of a neutron star into a black hole, for example, or perhaps a star exploding into a supernova. And it is possible that either of those events could produce the kind of burst seen from 121102 – but they could not do it repetitively. It was also considered that FRBs were likely to be coming from within our own galaxy or, if not within, then very close by. And that may still be the case – for other FRBs – but at a distance of more than 3 billion light years from Earth, it is clearly not the case here. (Our galaxy, which is known as the Milky Way Galaxy, has a diameter of between 100,000 and 180,000 light years). It is possible that 121102 is a magnetar, a kind of neutron star that has a very powerful magnetic field. Neutron stars are small, very dense, and created by the collapse of a star with insufficient mass to produce a black hole. But, when all of those caveats have been stated, it is also possible that some form of intelligence there is attempting to send a signal to intelligence elsewhere. *Excerpt from 'Where are They?' available here on Amazon

Excerpt from Chapter 3. Chapter 3 The Kardashev Scale Chapter 2 had some things to say about “civilisations” and “advanced civilisations”. But what are those things? What do we mean by “an advanced civilisation”? The Kardashev Scale is there to answer that question. Nikolai Kardashev is a Russian astrophysicist (he is still alive in 2017 at the age of 85). Born in Moscow in 1932, he graduated from Moscow State University at the age of twenty-two and began postgraduate studies in the University’s Sternberg Astronomical Institute, completing his PhD in Physical and Mathematical Sciences in 1962. In 1963, Kardashev took part in the first Russian search for extraterrestrial intelligence. While examining quasar CTA-102, he developed his ideas about what form extraterrestrial civilisations might take. They could, he realised, be ahead of anything on Earth by millions, and perhaps billions, of years. He developed the Kardashev Scale to define levels of possible civilisation. The original Kardashev scale had three levels (later researchers have added more). The most important thing to understand about the Kardashev Scale is that it is based on energy. As Kardashev sees it, the level a civilisation has reached can be measured by the amount of energy it consumes. In addition to energy, Kardashev focused on communications technology. (Those later researchers have also included other factors). In his paper, Transmission of Information by Extraterrestrial Civilisation, Kardashev said that an advanced civilisation would be able to transmit radio signals over great distances in space. The levels of civilisation he defined were:

How far are we earthlings from being able to become a Type 2 civilisation, capable of building a Dyson Sphere? Not, as these things go, very far at all; estimates are that we may be able to construct such a thing, and thereby make use of all the energy the Sun produces, between 1,000 and 2,000 years from now. 1,000 years ago, the Chinese were the first to use gunpowder in battle (and they had flamethrowers!). King Canute married his cousin Emma of Normandy, laying the seeds for the invasion of England by the Normans in 1066. Emperor Hadrian set up the first postal system and built a wall between England and Scotland. A thousand years isn’t very long at all. You won’t be here to see it, but it’s still very imaginable. It’s in the progression to a Type 3 civilisation that the number of years involved becomes monstrous.

By the time our earthly civilisation gets around to becoming Type 3, it’s likely that it won’t be a human civilisation at all. Humans will have disappeared, replaced by some kind of mechanised being. There will be more to say about that before this chapter ends, but before we go there, let’s take a look at what other theorists have suggested might be added to the Kardashev Scale. Kardashev listed only the three types of civilisation described above. Others have proposed more.

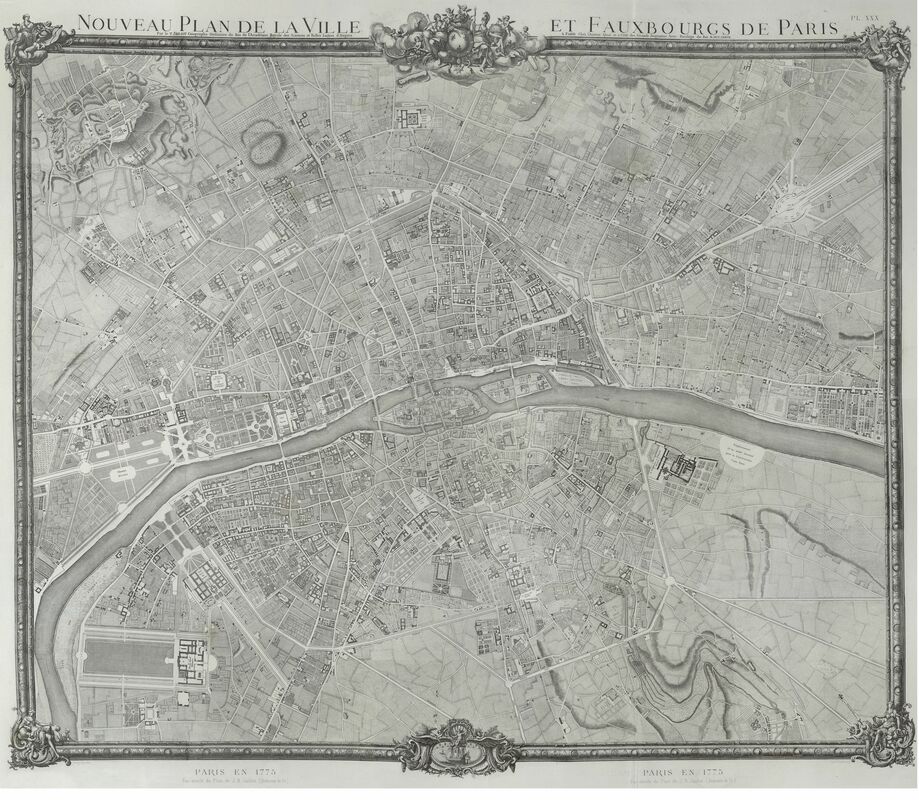

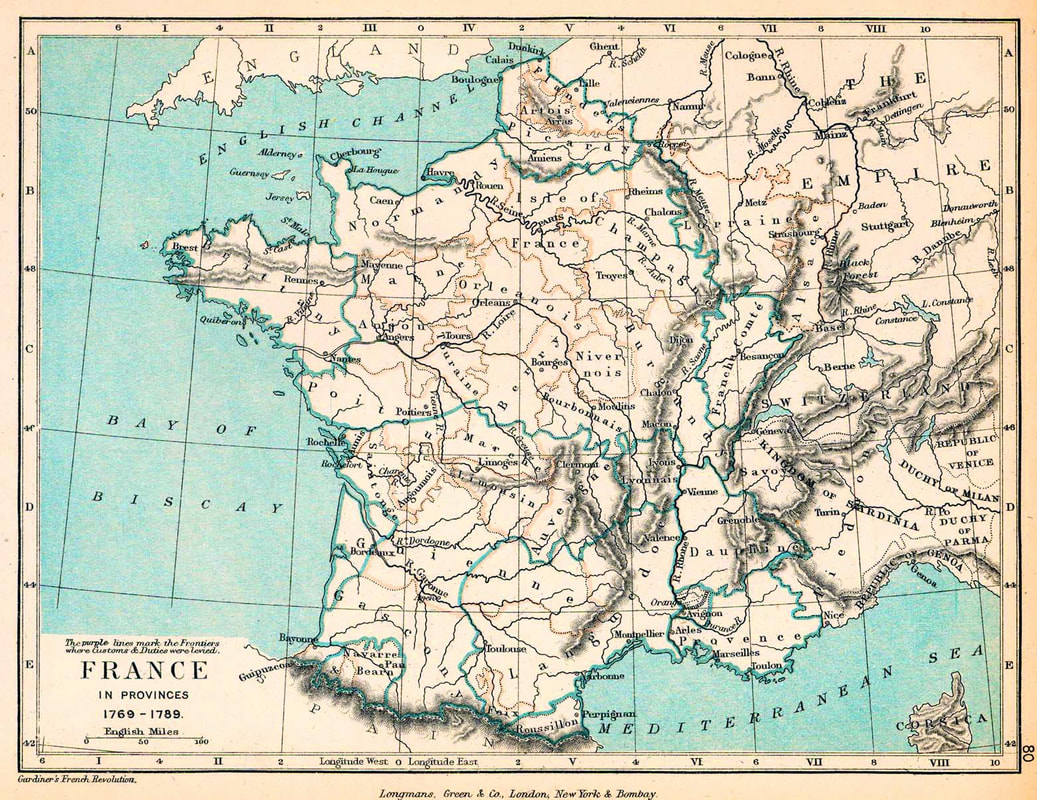

As it happens, some scientists have decided to add a Type 7 civilisation to the Kardashev Scale. What capabilities would a Type 7 civilisation have? There’s no point in even thinking about it. Step back to that Type 3 civilisation, and these words: By the time our earthly civilisation gets around to becoming Type 3, it’s likely that it won’t be a human civilisation at all. What can that possibly mean? We’ll be looking at this again in Chapter 9, but here are some of the ideas that are floating around. Read more about The Kardashev Scale here. So, I've been working on a manuscript for almost two years now. I don't wish to give away too much on the plot. Suffice to say it's a story of a man thrust at the dusk of the French Bourbon regime, about 15 years before the start of the French Revolution. His account of survival explores how a modern man can pick himself up with only the clothes on his back and survive in an era where life was brutally harsh , and the existence of social safety nets was non-existent. I have always been a fan of L. Sprague de Camp's story 'Lest Darkness Fall' - A story of a relatively modern man, from 1938, who inexplicably finds himself transported back in time to 535 AD (or for those of you who prefer CE) in the Eastern Roman Empire. Many stories have sprung from De Camp's initial foray into this form of alternative history writing. Notable writers who were influenced include Harry Turtledove, who writes many offshoots of alternative history. Examples include ideas such as the Byzantine Empire survives the Fall of Rome or how, in the middle of World War Two, the earth is invaded by a hostile alien species. Other writers influenced by De Camp include Frederik Pohl who wrote "The Deadly Mission of Phineas Snodgrass", a thought-provoking story of a man that travels back to 1 BC and teaches modern medicine, causing a population explosion. It ends with the fantastically overpopulated alternate timeline sending someone back to assassinate the title character, allowing darkness to fall for thankful billions. A similar story style to De Camp is "Outlander" written by Diana Gabaldon and now adapted for television by Ronald D. Moore. A story of Claire Randall, a married World War II nurse who, in 1945, finds herself transported back to 1743 Scotland, where she encounters the dashing Highland warrior Jamie Fraser and becomes embroiled in the Jacobite risings of Scotland. It was this most recent story that convinced me that a similar tale could be told with a focus on the 'Ancien Regime' era of France. I spent about 6 months researching the era of 1775 France, gathered up all my research notes and put together a story arc. Excited, I began banging away and put together a rough draft in the span of a couple of weeks. The story arc and the research helped give birth to the characters and the plot early on. Always a stickler for accuracy, I realised in the first rereading that I had missed some key dates in my storyline and certain characters were not historically accurately portrayed. There were glaring holes that I plugged, and there were events in the background of the story that were misplaced historically. Once they were analysed correctly, and following more historical research, I decided to change the starting date of the story to the 11th of May, 1774, the first day of the reign of Louis XVI, the last Absolute monarch of France. This date fused well with the other events, and characters I wished to introduce to the plot and subplot, so I had to go back and rewrite all the changes to take this new date into consideration. All in all a rather monumental task. No one ever said that writing was easy. A map of Paris 1775 Rereading the manuscript and getting feedback from those in my immediate circle who I trust, I quickly realised that the story could be improved by the introduction of a character in the 'modern era' tasked with determining the cause of the disappearance of the protagonist. Naturally, as the main character introduced changes to the timeline of the 18th century, the character tasked with the hunt for the truth finds himself in an ever-evolving world that reflects amplification of the changes wrought in the 18th Century. Another Beta reader (Thanks Nicky!) reminded me that my main character wasn't a monk, and needed a love interest. So a love interest was introduced. I had to research how a man 'courted' a bourgeoisie woman in this era, because naturally, how we do it in the modern world is entirely different. It's been quite a ride over these past two years. I'm almost ready to release it. If you want to learn a little something about France under the 'Ancien Regime' Id like to think you might pick up some historical knowledge while at the same time be entertained. Stay tuned for release dates. - Steven Lazaroff Map of France 1769-1789

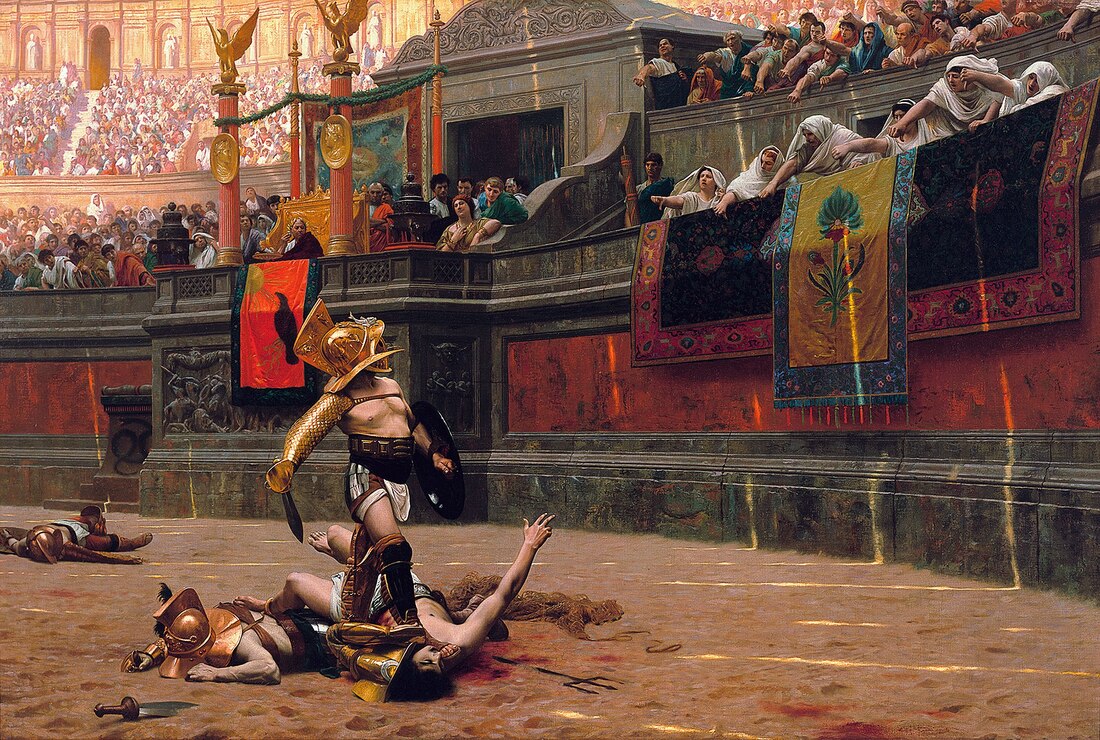

Hello Everyone! We are pleased to announce that Johnathan is out with his latest book, 'History's Greatest Warriors' - See below for an excerpt of the book. FLAMMA “The Gladiator” For many of us, the mere mention of the word ‘gladiator’ is synonymous with the mental image of actor and movie star Russell Crowe flailing around an arena, fighting for his life in the movie “Gladiator”. When compared to his historical counterparts, there’s actually very little resemblance to reality. Although many gladiators were slaves, some actually entered the arena of professional combat as volunteers, and none of them bore much resemblance to the Hollywood versions of the blood-thirsty fighters that have populated the silver screen over the years[1]. History and popular culture have made the name of Spartacus notorious as a romantic rebel ex-gladiator, but a truer champion of the gladiatorial Amphitheatre was Flamma. Professional gladiators were highly specialized and wore armour and weapons that demonstrated what specific style that they would fight in. Flamma was known as a secutor, specifically trained and equipped to fight a retiarius. The fights between these two types of reoccurring gladiators were based on the concept of a fisherman (the retiarius) fighting to catch the fish (secutor). As a result, the secutor’s armour would be designed to represent a fish’s scales and flowing contours, while the retiarius fought with a net and a trident but very little else. The light (or no) armour of the retiarius gave him scant protection but afforded him the advantage of having less weight to heave around the arena, providing a higher degree of mobility. In contrast, the secutor was heavily encumbered by armour, slower but better protected. In a match between these two common opponents, the slower, heavy fighter would have to try for an early victory before he collapsed of exhaustion[2]. It was in this regard that Flamma proved himself a champion over and over again. In addition to the secutor versus the retiarius, other gladiatorial contests were fought between murmmillo and hoplomachus; the double-handed swordsman, dimachaerus, pitted against the heavily armoured Oplomachus and scantily clad Bestiarius was an animal specialist that battled almost exclusively against exotic animals in a “man versus beast” special event combat. None of the authentic ancient gladiator types wore any kind of chest armour as is so often depicted in the movies. While he didn’t achieve the same notoriety of the Thracian gladiator Spartacus (his equipment would have included a thrax, or curved sword as well as a feathered helmet), Flamma was an imposing figure in the arena and fought valiantly over a 13-year period, repeatedly refusing to be granted freedom from gladiatorial life when offered the honor of the rudis – a wooden sword that was given as a high honor to the most successful and honored fighters. Although Spartacus may be the most famous gladiator people tend to know, Flamma demonstrated his fighting abilities in no less than 34 battles and new evidence is revealing more about him and his fellow professional combatants[3]. Contrary to the depictions of gladiatorial life that Hollywood has manufactured, professional gladiators were well trained and well looked after, representing a considerable investment by their owners (in the case of slaves) or managers. In today’s terms, they would be the equivalent of the most celebrated and successful professional sports stars. Gladiators were fed some of the best food available, and benefited from the best and latest medical treatments provided by leading physicians and healers. Unlike the ridiculous odds movie gladiators are seen to face in the arena, the real fighters like Flamma were carefully assessed and matched up with comparable fighters so that the combats were fair and balanced. Similarly, gladiators were not forced to fight over and over again and Flamma fought just 34 battles during his 13 years in the arena, averaging two to three clashes per year. These were shows – sports entertainment at the highest level, not slaughters. Recent findings by paleo-pathologist, Dr. Karl Grossschmidt indicate that the gladiators were kept in good health with a vegetarian diet that was heavy in carbohydrates. Unlike the chiselled, over-muscled bodies of today’s body-builders, Grossschmidt claims gladiators would have been carrying a bit of extra weight, partially as a form of protection and also because it made them look physically more impressive and intimidating. According to Grossschmidt, “Surface wounds “look more spectacular. If I get wounded but just in the fatty layer, I can fight on. It doesn’t hurt much, and it looks great for the spectators.”[4] While an intriguing theory, other scholars speculate that just like today’s professional fighters most would likely have tried to stay as slim as possible, avoiding extra fat that would just slow them down and impend performance. The specifics of the “gladiator diet” have always been a subject of debate. The grain barley has enjoyed a special focus, as it is believed that it assisted with building muscle, but there is conflicting documentation that suggests the leading physician of the time named Galen had certain reservations about it, fearing it was responsible for making the flesh soft”[5]. Similarly, artwork dating back to the gladiator era shows sinewy fighters with little evidence of the extra fat Grossschmidt believes was a hallmark of the profession. Writer David Black Mastro argues that the vegetarian diet the gladiators were fed reflects how unimportant they were. He claims that the lack of meat in their diets - even meat that was regularly consumed by others, indicates that they were given a poor diet to reflect their lowly status as slaves[6]. This is quite contrary to other opinions which indicate the gladiators enjoyed a celebrity status which is why some were volunteers, rather than slaves. The elite fighters who enjoyed popular support and frequent victories like Flamma, so enjoyed the fame and celebrity status that it became a difficult profession to leave. This seems to be the case with Flamma, as he was offered freedom four times and refused it so that he could stay in the public eye and keep fighting as a gladiator. While it’s true that as gladiators, these professional fighters were effectively confined and were not allowed to leave the gladiator camp of their own accord, it wasn’t all bad. Gladiators were permitted to receive visitors and - not unlike today’s sports superstars, there were groups of giggling girls all too eager to pay them a visit. These women were usually from highly respected families but would sneak into the camps to bestow their favours on the champions of the arena. Gladiators had groupies. While Grossschmidt compares the gladiatorial bouts to modern-day boxing, it enjoyed a rather different position in terms of how it was perceived as a pastime. We certainly don’t consider today’s boxing fans to be highly intellectual, but attending gladiatorial battles at the time was regarded as more sophisticated and respectable than another social activity - going to the theatre. The fights were seen as a celebration of important principles such as bravery and honour, while in comparison plays were “idle” entertainment. From this ancient Roman perspective, it is understandable how gladiators could be envied and idolized. Perhaps enjoying celebrity status was why Flamma repeatedly refused his freedom. Certainly, the vast majority of the gladiators were slaves and even those who had volunteered to fight could be bought and sold, as commodities. To most, having your freedom restored was considered an ultimate reward. This was symbolized by the rudis, a ceremonial token wooden sword that was presented to victorious gladiators who earned their freedom. The criteria for receiving this prize was highly subjective and was often granted at the whim of Emperors and other great and powerful men. Once a rudis was awarded, the gladiator was then allowed to walk through the “the gate of life” which meant he could leave the arena as a free man with no further obligation to fight. While most gladiators would win the rudis only once in their lives, Flamma was offered it four times and each time refused, returning to fight another day to the wild acclaim of adoring crowds. Flamma’s gladiatorial record is one of the longest and most distinguished we know about from the Roman records, spanning most of his adult lifetime. He made his professional gladiatorial debut at the age of 17 and went on to secure 21 victories in his 34 bouts. His fights ended in a tie only nine times, and after 13 years in the arena, he lost just four contests. The record of his success can be seen inscribed on his gravestone in Sicily where he is buried under the name, “Flamma of Syria”. Although the cause of death was not reported, one can only assume he died fighting. We know about his record exclusively from his grave marker. Today, headstones are generally arranged by family, but for the professional gladiator markers created to commemorate their remains were commonly prepared by the deceased’s colleagues and friends, as Flamma’s gravestone indicates. Inscribed with the epitaph “ Flamma, secutor, lived 30 years, fought 34 times, won 21 times, fought to a draw 9 times, defeated 4 times a Syrian by nationality” the stone bears an additional engraving which reads, “Delicatus made this for his deserving comrade in arms”[7]. There is no record of a gladiator by the name of Delicatus, and the word’s only association with the Romans appears to refer to homosexual practices. A puer delicatus was a young male slave who was chosen by his master according to this looks and his potential as a sexual partner. The relationship between master and puer delicatus was very different from the consensual relationship of the Greek paiderasteia. A puer delicatus was subordinate to his master in every way and essentially a sex slave. In some instances, the master was so enamoured with his puer delicatus that he would have him castrated and potentially, even marry him. The notorious Roman Emperor Nero married a young man named Sporus, his puer delicatus, in one of his several same-sex marriages[8]. It’s hard to be certain, but given this reference, it is possible that Flamma had a young boy of his own who worshipped him and subsequently requested the honour of creating the gravestone. A gladiator’s marker could be a testament to his life or an accusation after death, as it appears to be in the case of another gladiator that may have been a contemporary of Flamma. The grave of a fighter named Diodorus was discovered some 100 years ago in Turkey and is now on display at the Musee du Cinquanternaire in Brussels, Belgium. Born in Turkey, Diodorus fought there until his death but his headstone makes no reference to how many battles he won or lost. Instead, it reads: “After breaking my opponent Demetrius I did not kill him immediately. Fate and the cunning treachery of the summa rudis killed me.”[9]

Gravestones have revealed much about Flamma and his contemporaries, but the remains buried beneath them have told us much more. Researchers Grossschmidt and Dr. Fabian Kanz conducted a study of 67 skeletons discovered at Ephesus in Turkey. While learning much about these fighters’ diets, a variety of discoveries were made around the injuries that gladiators may have sustained, resulting in the conclusion that the combats they fought in may not have been quite as bloody and gory as was previously assumed. According to the pathologists, the lack of multiple injuries suggests that rather than engaging in a bloody free for all, the combatants fought under careful rules with referees ensuring the conflicts didn’t get out of control. It makes sense that in his 13-year career, Flamma would have sustained an injury or two and, without medical attention or the intervention of a match official probably would not have survived in the arena for so long. In keeping with the concept that the battles between retiarius and secutor reenacted the battle between Neptune, the god of water, and Vulcan, the god of fire, several of the skeletons uncovered in Ephesus show clear signs of having been stabbed with a three-thronged weapon, similar to Neptune’s famous trident. According to Grossschmidt, "The bone injuries - those on the skulls for example - are not everyday ones; they are very, very unusual and particularly the injuries inflicted by a trident, are a particular indication that a typical gladiator's weapon was used.” Additional evidence suggests that each bout was a one-on-one affair, with two gladiators facing each other with just one weapon each. It appears gladiators fought fairly and squarely for their triumphs and in the uncommon matches that were actually “to the death” - when they were literally fighting for their lives, they would be put out of their misery with a quick blow to the back of the head, delivered by an executioner who was hanging around in the wings for that very purpose. It was rare that one gladiator actually executed another. Other insights into gladiators and how they fought and died can be gleaned from ancient graffiti found among the ruins of the ancient city of Aphrodisias, situated near the modern-day village of Geyre in Turkey. Looking at these scribbled images of gladiators in battle, the most striking thing is how many appear to depict a secatuer in combat with a retiarius. The three-pronged Trident is a recurring image through the drawings, indicating this particular type of gladiatorial battle was among the most popular[11].

According to Professor Angelos Chaniotis from the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey, “Graffiti are the products of instantaneous situations, often creatures of the night, scratched by people amused, excited, agitated, perhaps drunk. This is why they are so hard to interpret," he said. "But this is why they are so valuable. They are records of voices and feelings on stone." In addition to insights into the arena and its contestants, the graffiti also show scenes of day-to-day life, including chariot racing and of course, sex[12]. As historians and researchers piece together these fragile fragments of an ancient civilization, they begin to reveal increasingly precise information about who the gladiators really were and what their lives were like both inside and outside the arena. One thing that is certain, is that these ancient warriors were very different than how they have been portrayed by the T.V. and film industry. Gladiators heroes like Flamma were courageous, violent men who were dedicated to their training and spent their short lives perfecting their techniques for the gratification of the audience, and for furthering fame and fortune. Their survival was perfecting their fighting prowess, and Flamma would have been as careful about his diet and lifestyle as any of today’s top athletes and soldiers. Risking probable injury, disfigurement, and death repeatedly and by his own choice, Flamma was the real gladiator, a warrior for the ages. Where Are They? And why haven’t we found them yet? by Steven Lazaroff and Mark Rodger

This could be the best non-fiction book I’ve ever read.I bought this book because I had previously bought and enjoyed History’s Greatest Deceptions and Confidence Scams. That book wasn’t perfect, but it was good enough that I wanted to see what they’d written next. And I am so glad I did. Where Are They? shows what happens when writers gain confidence in what they are doing. This book soars to the heights – both in its subject matter and literally, as a masterpiece in conveying information. The title comes from physicist Enrico Fermi who said, about theories that Earth should already have received extraterrestrial visitors and yet no convincing evidence of a visit existed, “Where is everybody?” The universe should be teeming with civilisations at one level of development or another – so where are they? The book examines all the current theories that have been developed to answer this question. It takes no sides. It simply sets out the present state of knowledge. But it does so in the most brilliant, beautiful prose. So brilliant that I would recommend this book even to readers with no interest in the search for alien intelligence, simply because they will enjoy the limpid prose and the humour with which the arguments are presented. Here is an example: ‘Imagine that you are in the same position as one of those alien astronauts being tapped up for a journey to Earth from the galaxy MACS0647-JD. It’s 13.3 billion light years away, so – if your civilisation has developed a form of transportation that will travel at the speed of light – the time spent on the journey is unimaginable. Would you want to do it? Leave the kids, your husband and your book club knowing that at the end of your journey you would encounter a civilisation a few hundred millennia less developed than yours? And that you couldn’t get home for nearly 27 billion years at the earliest, by which time your planet would in all possibility have come to the end of its life? And that, when you arrived on Earth, your body would have been renewed some eighty times, so you wouldn’t really still be you at all?’ Not a single prominent theory about the evolution of life forms has been left out. It’s also clear that the authors take a dim (they would probably say “realistic”) view of humanity’s fitness to receive visitors from another civilisation. I’ll say it again: this could be the best non-fiction book I’ve ever read. Do yourself the most amazing favour and READ IT. Return to Reviews of Other People’s Books Review by David Ben Efraim of Quick Review Books

Steven Lazaroff and Mark Rodger take the Logical Route Our society has most recently developed its tremendous fascination with outer space, largely due to the fact our observational and communicative technologies have advanced by nigh-incalculable leaps in the past decades. However, the allure of the stars always captured the imagination of our ancestors, even as primitive as cavemen if we are to judge by the paintings they left behind. We have been striving for countless years to gain a few more grains of knowledge on what lies beyond our Earthly realms, and if we take a look at the progress we have made in its totality, we would find it is both extremely significant and insignificant at the same time. We might know a lot more than we once did, but it still remains virtually nothing in the grand scheme of things. Nevertheless, Steven Lazaroff and Mark Rodger have decided to compress this sum of human knowledge into a book titled Where Are They?. The first thing I should mention, this is a non-fiction book and its aim is to explore as profoundly as possible both sides of the argument debating on the existence of aliens and our likelihood of ever meeting them. In order to do so, it begins with hypothetical explorations of the many different scenarios which might result from us encountering aliens in the future. Following that, they take a more grounded approach as they examine the various efforts we've made in an attempt to find alien life forms as well as the theories we have developed over time. The book then expands into evolutionary theories which might account for both the existence or inexistence of aliens. For the final stretch, the authors focus on where they believe the road ahead might lead us and what we ought to expect based on what we have witnessed on Earth. A Light Read on a Heavy Topic It should go without saying the science of space exploration is extremely complicated, involving various fields such as cosmology, physics, biology, and probably many more with names I could never hope to remember. Somehow, the authors have managed to do away with the overwhelming majority of complicated stuff and have laid things out in layman's terms. Even the more complex theories, calculations and philosophies are explained in a very simple and intuitive manner, and I believe this is one of the main reasons I enjoyed this book so much. As much as I would love to know all the intricacies behind the calculations at the SETI Project or the profound implications of isolationism, I accept they are more than a tad beyond me, unless of course I have countless hours to dedicate to their study... which I don't. In my previous non-fictional readings on the subject of aliens, I often found the authors either kept things far too simple and surface-level, or they dove so deeply into the technical details they were never seen again. This book feels like it strikes the perfect middle ground between the two, as I never had any problems progressing or felt the need to re-read what I just went through for comprehension purposes. I always had a good understanding of what the authors were trying to depict, and what's more, I really felt like I was learning from one page to the next. Perhaps it has to do with the authors' slightly humorous and easy-going style, but the information never had any problems sticking in my mind. The Unbiased Perspective Authors who write on the subject of aliens generally have their minds set on a certain theory or scenario they believe to be the likeliest... and are thus biased in their dissection of the subject. While I wouldn't say the authors here have achieved complete and utter neutrality (their passion for the possibility of alien life existing briefly manifests itself from time to time), they have come closer than most. I never got the sense they were trying to push something down my throat or guide me along a specific path to shape my beliefs. They do a fantastic job of setting their own notions aside for the most part, simply delivering the cold, hard facts and renowned published theories. I felt this even held true for the more philosophical parts of the book where the authors explore the various possible implications of first contact, technology exchange, or us being alone in the universe, just to name a few. Would the elite seek to hoard knowledge and technology from the aliens? Developmentally-speaking, are we prepared for the moral responsibilities of incredible advancements? They raise some very interesting points which I found pushed me to do further research, rather than jump to any conclusions. Ultimately, I feel the authors truly want to educate their readers, providing them with the resources and curiosity necessary to delve deeper into the subject and perhaps even develop their own theories on the matter. After all, while we might know more than we once did, we still know virtually nothing in the grand scheme of things... a thing Lazaroff and Rodger always keep in mind. The Final Verdict All in all, Where Are They? by Steven Lazaroff and Mark Rodger is probably the most engaging and reader-friendly nonfiction book on aliens I have had the pleasure of reviewing, at least in recent memory. It's written in a slightly humours and easy style and covers all the bases of our search for alien life without going in too deep but still providing a big enough wealth of information. If you are even remotely interested in aliens what humanity has accomplished in its search for them, then I strongly recommend you give this book a shot. The term “scam” is really a new word in the English lexicon and has come to supersede its older and more distinguished original cousin, “the confidence game” or “con game”, as it became popularly known at the time. One constant in human history is the tendency to want to shorten and simplify some of the most descriptive concepts we have, to anything that can be mumbled as a single syllable mouthful.

Throughout history, there have always been fraudsters and tricksters ready and willing to part people from their money with smooth talking and tall tales, but the first formally recorded “confidence trick” was uniquely American in its origins and set the bar for both simplicity and sheer guts, both hallmarks of the most successful frauds ever perpetrated. In the late 1840’s the east coast of the United States was awash with the nouveau riche, and men wearing top hats to look important. Good manners and polite society were everything unless you were a slave in which case the top hat was entirely optional. It was the age of Jane Austen, white gloves, carriages and over-the-top manners. It was also the time of pocket watches, dangling from gold chains. Victorian sensibilities dictated that the bigger and shinier the watch, the bigger and shinier the man. Enter one William Thompson, arguably the originator of the term “confidence man”, a genius operator and a personal hero to the career grifter. Little is known about where he came from, but what is certain is that he had his finger on the pulse of well-heeled suckers strolling the walkways and avenues of Manhattan in the mid-nineteenth century. Meeting someone was a rigid, formal affair with protocol and procedures; the handshake, tip of the hat and bow were rigidly choreographed. Failure to introduce oneself properly or be introduced according to accepted custom was seen as an embarrassment to both parties – and embarrassment was worse than a bleeding head wound, to be avoided at all costs. Operating in New York in the 1840s, William was a keen observer of human behaviour. He realized that, with such pomp and ceremony surrounding every introduction, it was considered the ultimate in bad manners not to remember people that one might have been acquainted with – he calculated that when confronted with a stranger that said he was a friend, most men would likely act as though they remembered a meeting that had never happened. William thought he might be able to leverage this, and so would often stroll along the city streets, until he spotted an upper-class sucker, at which time he would approach and pretend to know them and be a past acquaintance, someone that they had met before. Rather than be embarrassed, the mark would usually smile, nod and pretend that he knew who William was – better that than risk dishonour, or a pistol duel – which was how some matters of honour were settled at the time. After some friendly chatting, and a little trust-gaining, Thompson would throw out his hook, asking “Have you confidence in me to trust me with your watch until tomorrow?” He wasn’t all about watches – sometimes he would ask for money. It’s good to diversify. More often than not, the mark would part with the watch or the money (or sometimes both) and William would depart, promising to meet the next day to return the property. Naturally, he didn’t keep the next day’s appointment and would often stroll away, laughing to himself. He repeated this game dozens of times until he had the bad luck to happen across a former victim, who promptly summoned a roving policeman who gave chase. After a frantic foot pursuit through Manhattan and a dramatic struggle, William was bodily subdued and arrested. Perhaps he was slowed down by the weight of all those pocket watches; it was reported that he had several on him at the time he was caught. His arrest and the subsequent article in the New York Herald called “Arrest of the Confidence Man” made headlines across the country; he was headed to trial in 1849. The press noted his specific appeals to victims’ “confidence” and thereafter he was known in the press as “The Confidence Man”. And so the term was born, and “confidence game” or “con” became part of our vocabulary, and spawned an endless series of quick-buck fraudster copycats that said, “me too”! This is the story of some of the greatest. Get your copy here http://bit.ly/2Qj0mVv Some discussions in some facebook groups that I belong to have centered on the subject of religion, so I thought I'd include an excerpt from our book that discussed the religious angle.

And those trade arrangements of the past were very one-sided. If our experience with extra-terrestrials mirrors that of peoples colonised by Europeans, “trade” will not be something conducted by equals – Earth will have resources that the aliens need and what they will offer in return will amount to the equivalent of glass beads. But then, it’s as well to remember that the kind of civilisation imagined here is likely to regard an iPhone X as the equivalent of glass beads. A close look at European colonial history suggests other possibilities, too. Earth may be invaded to spread religion, as many countries on this planet were invaded to force people to adopt Christianity. Or Islam. Or Communism. And that brings us back to the question of how people will respond. This will be dealt with in more detail later in this book, but it is often suggested that one of the big losers on Earth in the event of discovery of an extra-terrestrial civilisation would be religion. And that is not, in fact, necessarily so. A cartoon doing the Facebook rounds recently showed some aliens on another planet talking to visitors from Earth. ‘Jesus?’ says one of the aliens. ‘We know him well. He drops in about once a month. We give him coffee and cakes. How did you treat him?’ Suppose the invaders brought with them a holy book that told roughly the same story as the Bible. Or the Quran. Or some other religious text already known here. Is it possible to imagine anything that could better reinforce an existing religious message? Then again, there’s the possibility that the extra-terrestrials’ values are so far from those of humans that it is impossible for humans to understand them. Earth provides a fairly benign environment for the human race to grow up in. When humans have been able to desist from killing each other, in the cause of religion or trade or simply because humans are tribal and don’t really like people from other tribes, the world has mostly been kind to them. Imagine a different planet – the one from which the inter-stellar visitors are coming – in which every day is a struggle for survival. These aliens did not emerge unscathed from their own planet’s evolution. They survived because they became better at killing other species than other species became at killing them. What mindset – what value system – are such people likely to have developed? It’s extremely likely to be the idea that the universe is predicated on the survival of the fittest. They believe that, if humans are unable to resist them effectively, humans are not fit for survival. They would be justified in killing us, just because they could. Justified not, perhaps, by our standards and values, but certainly by theirs – and it would be their standards and values that counted, because “might is right.” 'Where are They?' is available now on Kindle ana paperback. Get your order here. |

AuthorMark Rodger and Steven Lazaroff live in Canada. Archives

July 2020

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed